One of the clearest videos of my astrobiology lecture was recorded when I spoke at the Liverpool John Moores University in November 2013. Here it is on YouTube.

Category: Academic Work

Lewis Dartnell discusses how extremophiles have pushed the survival envelope of terrestrial life – and what this means for the possibility of extraterrestrial life.

Lewis Dartnell discusses how extremophiles have pushed the survival envelope of terrestrial life – and what this means for the possibility of extraterrestrial life.

Download pdf

Also available at Astronomy & Geophysics

Mark Burchell and Lewis Dartnell review the current standing of astrobiology research in the UK, and look to future success.

Mark Burchell and Lewis Dartnell review the current standing of astrobiology research in the UK, and look to future success.

Download pdf

Also available at Astronomy and Geophysics

On Earth, microbes get absolutely everywhere. Indeed, there seem to be very few completely sterile natural environments. But what about microbial colonization of locations beyond Earth? In this article we’ll explore the realm of space bugs. There is a great deal of interest in the microbiology of the closed artificial environments created for human exploration of the cosmos, such as the International Space Station (ISS), as well as in minimizing the risks of inadvertently transporting terrestrial contamination elsewhere, and even the possibility of a natural mechanism spraying life between worlds over the history of the solar system.

On Earth, microbes get absolutely everywhere. Indeed, there seem to be very few completely sterile natural environments. But what about microbial colonization of locations beyond Earth? In this article we’ll explore the realm of space bugs. There is a great deal of interest in the microbiology of the closed artificial environments created for human exploration of the cosmos, such as the International Space Station (ISS), as well as in minimizing the risks of inadvertently transporting terrestrial contamination elsewhere, and even the possibility of a natural mechanism spraying life between worlds over the history of the solar system.

Download pdf

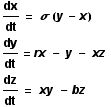

The Lorenz equations are a set of three coupled non-linear ordinary differential equations (ODE). They make up a simplified system describing the two-dimensional flow of a fluid. As can be seen, the derivative of all three variables is given with respect to t, and as a function involving one or both of the other variables (thus they are said to be coupled). The usual values taken by the parameters are as follows:

The Lorenz equations are a set of three coupled non-linear ordinary differential equations (ODE). They make up a simplified system describing the two-dimensional flow of a fluid. As can be seen, the derivative of all three variables is given with respect to t, and as a function involving one or both of the other variables (thus they are said to be coupled). The usual values taken by the parameters are as follows:

sigma = 10, r = 28, and b = 8/3.

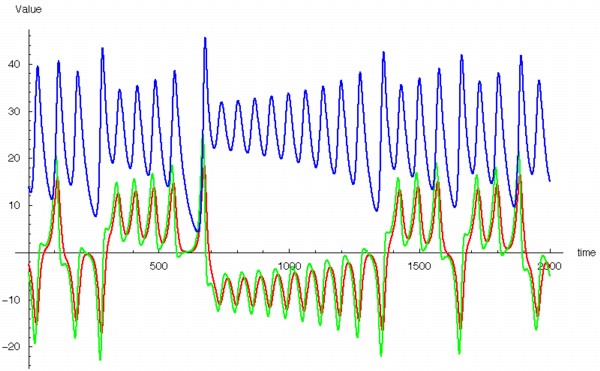

As time is incremented then, the calculated values of x, y, z change as shown in the timeseries plot below. x = red, y = green, z = blue.

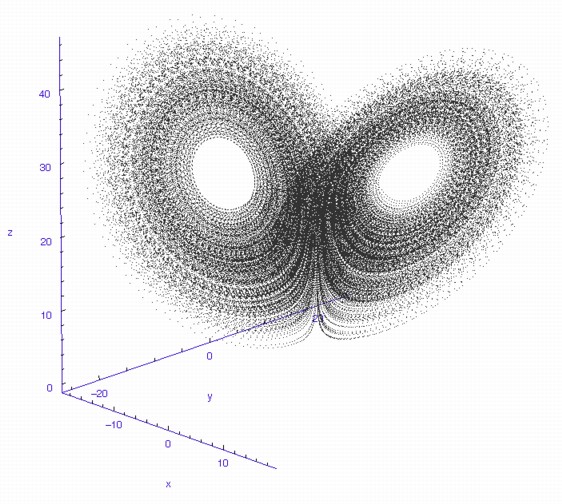

The fluctuations are seemingly utterly random. More structure can be seen, however, if the same timeseries is plotted as a sequence of co-ordinates describing a trajectory through 3-space. As shown to the right, the surface resembles a twisted bow-tie. It is known as the Lorenz strange attractor, and no equilibrium (dynamic or static) is ever reached – it does not form limit cycles or achieve a steady state. Thus, no trajectory ever coincides with any other. Instead, it is an example of deterministic chaos, one of the first realised by mathematicians.

The fluctuations are seemingly utterly random. More structure can be seen, however, if the same timeseries is plotted as a sequence of co-ordinates describing a trajectory through 3-space. As shown to the right, the surface resembles a twisted bow-tie. It is known as the Lorenz strange attractor, and no equilibrium (dynamic or static) is ever reached – it does not form limit cycles or achieve a steady state. Thus, no trajectory ever coincides with any other. Instead, it is an example of deterministic chaos, one of the first realised by mathematicians.

One of the properties of a chaotic system is that it is sensitive to initial conditions. This means that no matter how close two different initial states are (i.e. even down to the 20th decimal place) their trajectories will soon diverge. This is popularly referred to as the “Butterfly Effect”, whereby small changes in the initial state can lead to rapid and dramatic differences in the outcome. The metaphor is that a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil could result in a tornado in Texas.

The Lorenz equations cannot be solved analytically by integration. Instead, a numerical approximation technique must be used. The 4th order Runge-Kutta (RK) method employed here takes a weighted average of four estimates of the derivative at a point in order to calculate the new position after a time increment. The lower-order error terms cancel out, making RK very robust despite its simplicity.

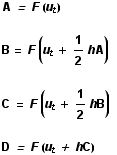

To generate all of these images and animations, a Mathematica programme was written to perform the RK numerical analysis of the Lorenz equations. For the initial state, an arbitrary point in 3-space, ut , is chosen, and then four derivatives calculated (A, B, C and D) using a time increment of h. In each case, F is the three-dimensional vector function composed of the Lorenz differential equations given above. These derivatives are weighted and combined to give the approximation for the next point, ut+h .

To generate all of these images and animations, a Mathematica programme was written to perform the RK numerical analysis of the Lorenz equations. For the initial state, an arbitrary point in 3-space, ut , is chosen, and then four derivatives calculated (A, B, C and D) using a time increment of h. In each case, F is the three-dimensional vector function composed of the Lorenz differential equations given above. These derivatives are weighted and combined to give the approximation for the next point, ut+h .

The three components of this point are appended to a storage list, and then the whole calculation reiterated a large number of times. For the high resolution image above, 100,000 co-ordinates were calculated and plotted, expending almost an hour of computer runtime. For the animation below, only 10,000 points were used.

Once calculated, all of the points in this data list are plotted in order to visualise the Lorenz attractor. This draw command was placed in a programme loop, with the x, y, and z co-ordiantes of the viewing-point for the projection incremented each time to generate a string of images. These were then converted into an animated .gif to create the rotating attractor shown to the left.

Once calculated, all of the points in this data list are plotted in order to visualise the Lorenz attractor. This draw command was placed in a programme loop, with the x, y, and z co-ordiantes of the viewing-point for the projection incremented each time to generate a string of images. These were then converted into an animated .gif to create the rotating attractor shown to the left.

The animation of the trajectory through time (shown at the top) was created by calculating just 1,000 co-ordinates, starting with a point known to be near the transition region between the two lobes. Only a subset of these points were plotted each time in the draw loop, beginning with the first 5, then the first 10, first 15, 20, 25, and so on.

The humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae, produces the most complex vocalisations of all 77 cetacean species, which have been dubbed by Payne and MacVay (1971) as “songs”. These songs are hierarchical in nature, with rules seemingly governing their organisation and evolution over breeding seasons. No one hypothesis of the song’s function adequately explains its complexity and structure, except perhaps for the theory that it constitutes the first non-human language yet discovered. Buck and Suzuki (1999) have applied Information theory to analyse a sample of humpback song converted into a stream of symbols using a self-organising neural network (SONN). This theory can be used to determine the maximum amount of information contained within a coded sequence by the unpredictability of the next symbol. Different assumptions can be made about the nature of the sequence; the next symbol is randomly determined (thus no hierarchical structure is possible within the sequence), or the probability of the next symbol is dependent on the previous one, or two symbols (0th, 1st and 2nd Order Markov models respectively). It was found that a first-order assumption could not reasonably model humpback song, meaning that humpback song possesses a hierarchical structure suggestive of language. The low rate of information transmission, about 0.1 – 0.6 bits per second, may ensure reliable communication over long distances in noisy, unpredictable acoustic conditions.

The humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae, produces the most complex vocalisations of all 77 cetacean species, which have been dubbed by Payne and MacVay (1971) as “songs”. These songs are hierarchical in nature, with rules seemingly governing their organisation and evolution over breeding seasons. No one hypothesis of the song’s function adequately explains its complexity and structure, except perhaps for the theory that it constitutes the first non-human language yet discovered. Buck and Suzuki (1999) have applied Information theory to analyse a sample of humpback song converted into a stream of symbols using a self-organising neural network (SONN). This theory can be used to determine the maximum amount of information contained within a coded sequence by the unpredictability of the next symbol. Different assumptions can be made about the nature of the sequence; the next symbol is randomly determined (thus no hierarchical structure is possible within the sequence), or the probability of the next symbol is dependent on the previous one, or two symbols (0th, 1st and 2nd Order Markov models respectively). It was found that a first-order assumption could not reasonably model humpback song, meaning that humpback song possesses a hierarchical structure suggestive of language. The low rate of information transmission, about 0.1 – 0.6 bits per second, may ensure reliable communication over long distances in noisy, unpredictable acoustic conditions.

The suborder Microchiroptera contains approximately 800 species of bats with a sophisticated biosonar system used to actively interrogate the local environment and analyse the retuned echoes to extract information on obstacles and potential prey in the flight path. Most are insectivorous and hunt with aerial-hawking or gleaning tactics, although some, such as Noctilio leporinus, predate on fish and use echolocation to detect localised surface ripples. Much research has been conducted into the neurophysiology of echolocation with its superb acoustic discrimination capabilities, including very fine temporal and frequency resolution. This review covers firstly bat call design and hunting behaviour, and the neural basis of their capabilities. The second half deals with the question of a bat-moth co-evolutionary arms race.

The suborder Microchiroptera contains approximately 800 species of bats with a sophisticated biosonar system used to actively interrogate the local environment and analyse the retuned echoes to extract information on obstacles and potential prey in the flight path. Most are insectivorous and hunt with aerial-hawking or gleaning tactics, although some, such as Noctilio leporinus, predate on fish and use echolocation to detect localised surface ripples. Much research has been conducted into the neurophysiology of echolocation with its superb acoustic discrimination capabilities, including very fine temporal and frequency resolution. This review covers firstly bat call design and hunting behaviour, and the neural basis of their capabilities. The second half deals with the question of a bat-moth co-evolutionary arms race.